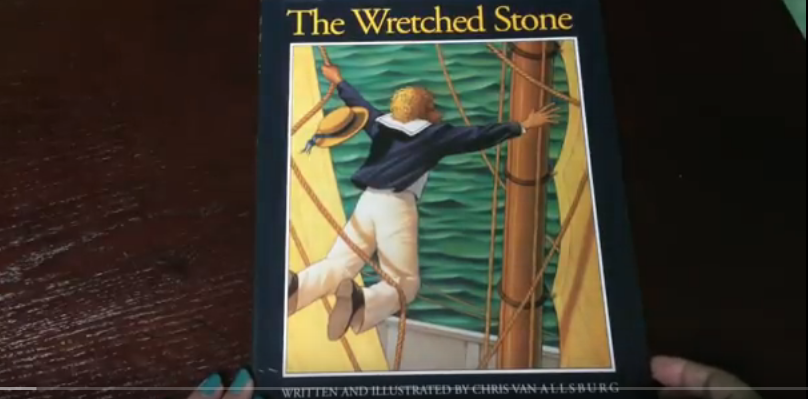

Book: The Wretched Stone written and illustrated by Chris Van Allsburg, published by Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991.

Category: Picture book, fiction concept book.

Overview of the author/illustrator:

Although Chris Van Allsburg did not receive a Caldecott medal for this particular work, he is the beloved author of Caldecott Honor Medal book The Garden of Abdul Gasazi and two very well-known and big screen adapted books: Jumanji and The Polar Express, both of which were Caldecott winners. Allsburg is also the recipient of the the Regina Medal for lifetime achievement in children’s literature. Allsburg began as a sculptor, and with encouragement and inspiration from his elementary school teaching wife, eventually went on to write and illustrate children’s books of his own. Like many children’s authors, Allsburg has a goofy sense of humor and on his own website describes himself by saying: “Chris lives in Beverly, MA, on Boston’s North Shore. For recreation and amusement, he rides his bike and plays tennis. He is not really the master of any instruments, but can entertain his children by producing simple tunes playing a recorder through his nose,” (2015).

Brief Summary:

The Wretched Stone is a book with an interesting format: it tells the story of a captain and his crew on their adventures in the form of a captain’s log. The captain of the ship stumbles upon a peculiar object when docked one day, and when he brings it back to the ship his crew experiences some interesting changes, and it becomes his mission to change them back into the fun-loving people they used to be.

Connections:

[All images have been screen captured from Heidi Weber’s (2017) YouTube channel read aloud video and have been referenced at the bottom.]

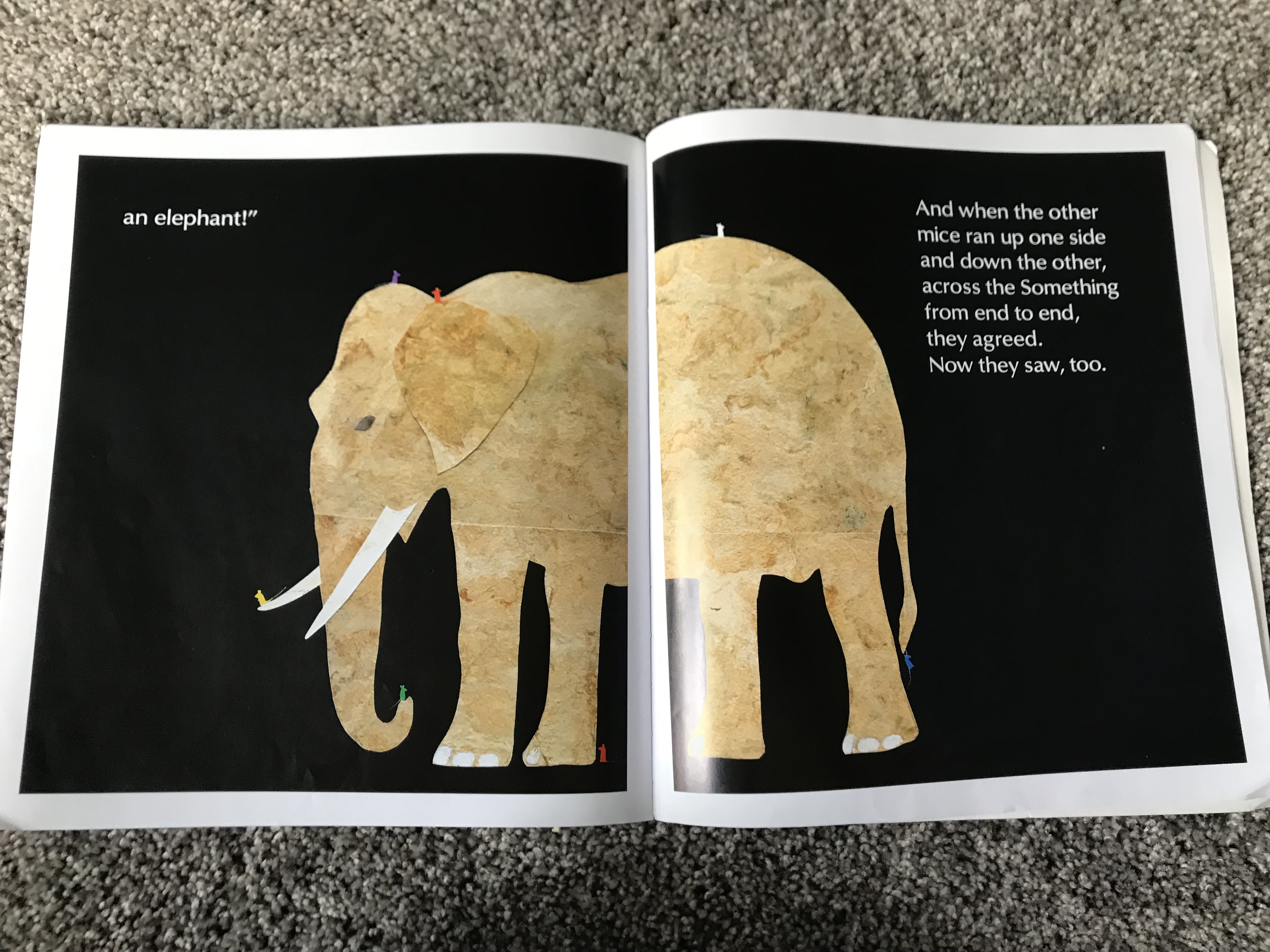

This fantastical book opens with no other information other than the captain beginning his log of his current voyage. The illustrations in this story are especially important because we are transported to a fantasy world with characters unlike any other.

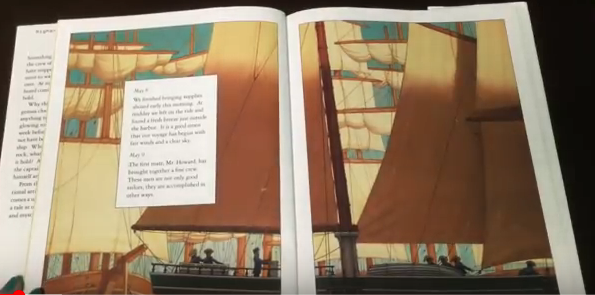

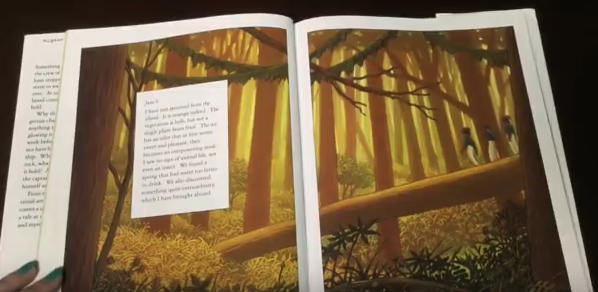

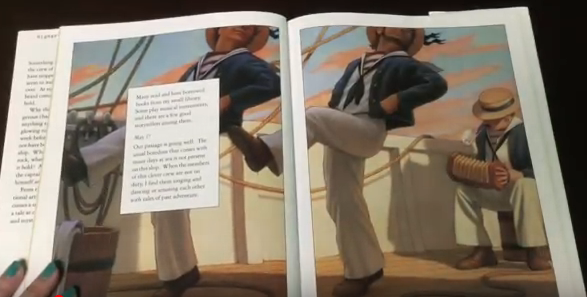

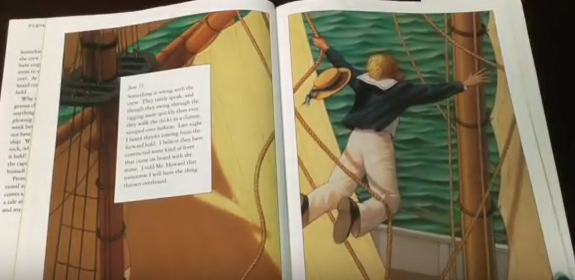

The use of line is important to note in Allsburg’s illustrations, as objects that would normally be depicted with straight, rough lines are shown with smooth, rounded edges. Everything from the boat on which the crew sails to the trees in the unknown forest, to the members of the crew are given a glossy, almost doll-like look. The use of these rounded edges makes this eerie tale more accessible to children, and it also transports us more easily into Allsburg’s imagined land.

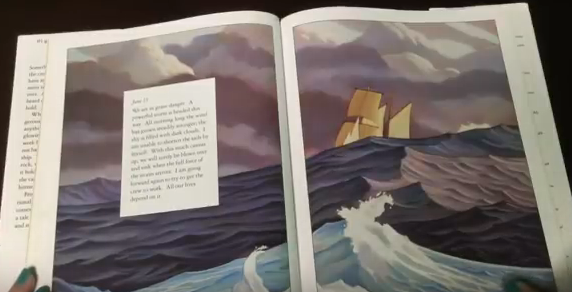

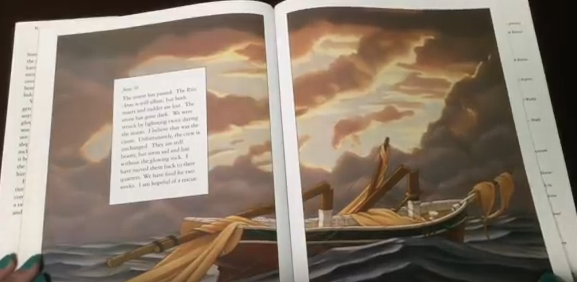

The illustrations are also used to develop and extend the plot. We are told mostly the facts by the ship’s captain, when he says things like: “Our passage is going well. The usual boredom that comes with many days at sea is not present on this ship,” and “The storm has passed. The Rita Anne is still afloat, but both masts and rudder are lost,” (Allsburg, 1991). Allsburg is able to bring these sentences to life with his illustrations: men in colorful uniforms marching gaily on the ship’s deck with a man playing a accordion; and the total destruction of the ship shown with the storm clouds breaking, masts broken, barely held up by the rough waters below.

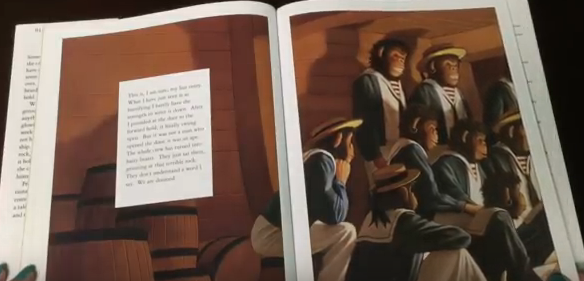

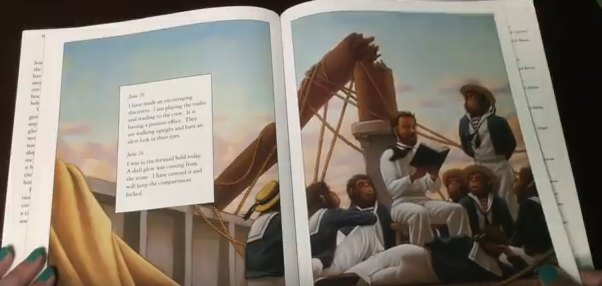

Allsburg’s purposeful use of composition is evident as well. Breaking from a traditional style of picture book where the words caption the illustrations, the captain’s logentries are placed directly on the pages throughout, reminding us as we read the story who is narrating. Allsburg is also deliberate in not showing us the crew member’s faces until they are turned into apes: the beginning page showing us only the bottoms of their faces and a crew member who is hidden by a hat, crew members walking along a log out of view of the reader or with their backs turned on the top of the ship, a crew member who appears to “swing through the rigging more quickly than ever,” (1991) but with his back still turned to us, to even the captain of the ship as he walks up the stairs – his face, of course, still not visible. Even the crew members on land at the very end are shown with their backs to us. Perhaps this is because Allsburg wants us to be fully shocked by their transformation into apes, or perhaps it is because their faces are not the focus of the story until they become apes, and therefore it is not important to show it.

Or perhaps it is because the illustrations carry the story, they depict action, “One of the ways picture book artists create tension in their work is by using illustrations to anticipate or foreshadow actions,” (Tunnel, et al. 2016, pg. 43) and Allsburg certainly leaves the reader feeling tense. The reader feels the mood of the story with the ship’s abandoned deck in the dark hues of blue depicting a somber and creepy feeling; and again when we are warned of the upcoming storm with the dark blue waters contrasted by light blue crashing waves and a dreary, cloudy sky.

The way Allsburg refuses to show their faces leaves us wondering why, until we finally see the crew members as apes, sitting around the stone, gazing intently. Allsburg is careful here too – he never shows us the glowing stone, leaving it up to the viewer and their own imagination to figure out what it may truly look like. Though a description is given: “It is a rock, approximately two feet across. It is roughly textured, gray in color, but a portion of it is as flat and smooth as glass,” (Allsburg, 2016) there is much left up to interpretation as Allsburg refuses to show it to us.

Finally, Allsburg’s personal style is apparent through the whole book, his illustrations creating depth with their incredible attention to detail. Allsburg’s surrealist illustrations captivate the reader, reminding us that we’re in a fantasy-world, but one not too much unlike our own world. Although Allsburg doesn’t show us the glowing rock or the crew member’s faces, he does provide important details that give depth to the story: crew member’s heads titled back in delight; the overgrown forest where the rock was found, shrouded in vines; the colors seen in the rough waters and the fluffy but ominous rainclouds; and the intent stares of the crew member’s faces when they are finally shown to us – first staring into the glowing rock, and then as the ship member reads them a story. Tunnel, et. al remind us that “It is not difficult to see tat details in illustrations tend to give the artwork depth and allow artists to assert their individuality,” (2016). This is obvious throughout all of The Wretched Stone in Allsburg’s unique way of showing us his imagined world.

Conclusion:

I categorized The Wretched Stone as a concept book because to me at least, it seems to paint a pretty obvious moral: people change based on their surroundings. When they didn’t have the stone to gaze at, the crew members danced, sang, played instruments, and told stories. When they had the stone – their experience changed, and they became different people: in this scenario, monkeys. People adapt to their surroundings, and it changes them. This relates rather perfectly to social constructivist theory, which tells us that people are shaped by the ideas and actions of those around them. People who grow up in different areas ideas are formed differently, and it’s something important to consider especially in teaching, but also in daily lives when we form opinions about others. I found myself thinking: is the glowing stone a metaphor for a television? When people are given the option to sit around this “glowing rock” all day, full of rapidly changing pictures, will they choose to sing and dance? To write and read? A child who grows up in a home and a school environment that is full of rich literature – how will their experience differ from one that is devoid of books, and features instead: a glowing rock? And the most pertinent question of all: in a society shaped so much by technology, how do we find balance?

References:

Chris Van Allsburg: biography. Allsburg, C., A. (2015). Retrieved June 13, 2019, from https://hmhbooks.com/chrisvanallsburg/biography.html.

Tunnell, M. O., Jacobs, J. S., Young, T. A., & Bryan, G. (2016). Children’s Literature, Briefly (6th ed.). Upple Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

The Wretched Stone (Read Aloud). Weber, H. (2017, May 16). Retrieved June 13, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNHEXJj_WVA&t=29s.