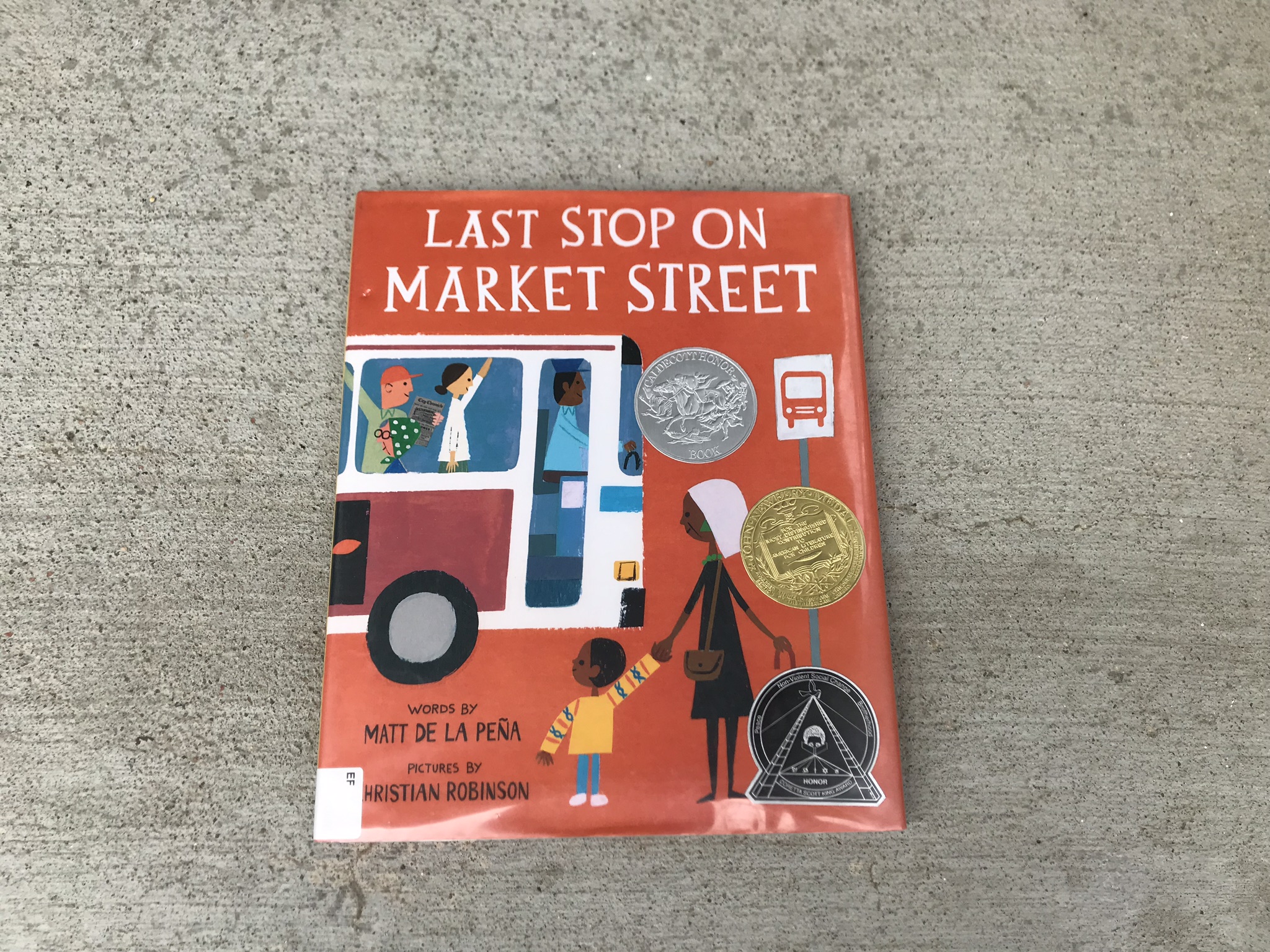

Book: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña illustrated by Christian Robinson, A 2016 Caldecott Honor Book, 2016 Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor Book, New York Times Book Review Notable Children’s Book of 2015, Wall Street Journal Best Children’s Book of 2015

Focus of Book: Contemporary realistic fiction, picture book

Overview of author: Matt de la Peña is an award winning author of children’s and young adult literature, who describes himself as a basketball junkie. De la Peña figured out when he was younger that he had a better chance of being able to get a scholarship to college due to athletics than academics, so that was the road that he took. He does say that he, “wrote secret spoken word poetry in the back of class,” and that he was influenced heavily by his 11th grade English teacher who, “told me I was a great writer. And even though I didn’t believe her at the time, I loved her class,” (Bartel, J., 2015). De la Peña is half Mexican and half white, and he says that it, “puts me in an interesting place in the call for more diversity in books for young people,” (Bartel, J., 2015). De la Peña writes about diverse characters in a way that race is evident, but not the entire plotline of the story – writing stories about social issues with themes of race, class, inequality, poverty, and more, through a lens that is accessible to younger readers.

Overview of illustrator: Christian Robinson is an award winning children’s illustrator who has also worked as an animator with Pixar and The Sesame Street Workshop, who always loved creating when he was a child. He says, “Creativity allowed me to be in charge, to make my own rules, and create my own little world on paper,” (2018). Robinson says he loves to make collages, and that Last Stop on Market Street was made with a mix of paint and collage, and that his enjoyment comes from trying out all kinds of new things and techniques.

Summary of the book: Last Stop on Market Street is a book about a little boy who takes the trip with his grandmother after church to volunteer at a soup kitchen. He spends the trip pondering various questions out loud to his grandmother: why don’t they have a car? Why do they have to go somewhere after church every Sunday? Why are some people blind? Why does the area of town that the soup kitchen is in look so run-down and dirty? His grandmother answers his questions thoughtfully and beautifully, and allows CJ to see the world through a lens he was not previously used to looking through.

Connections:

Contemporary realistic fiction:

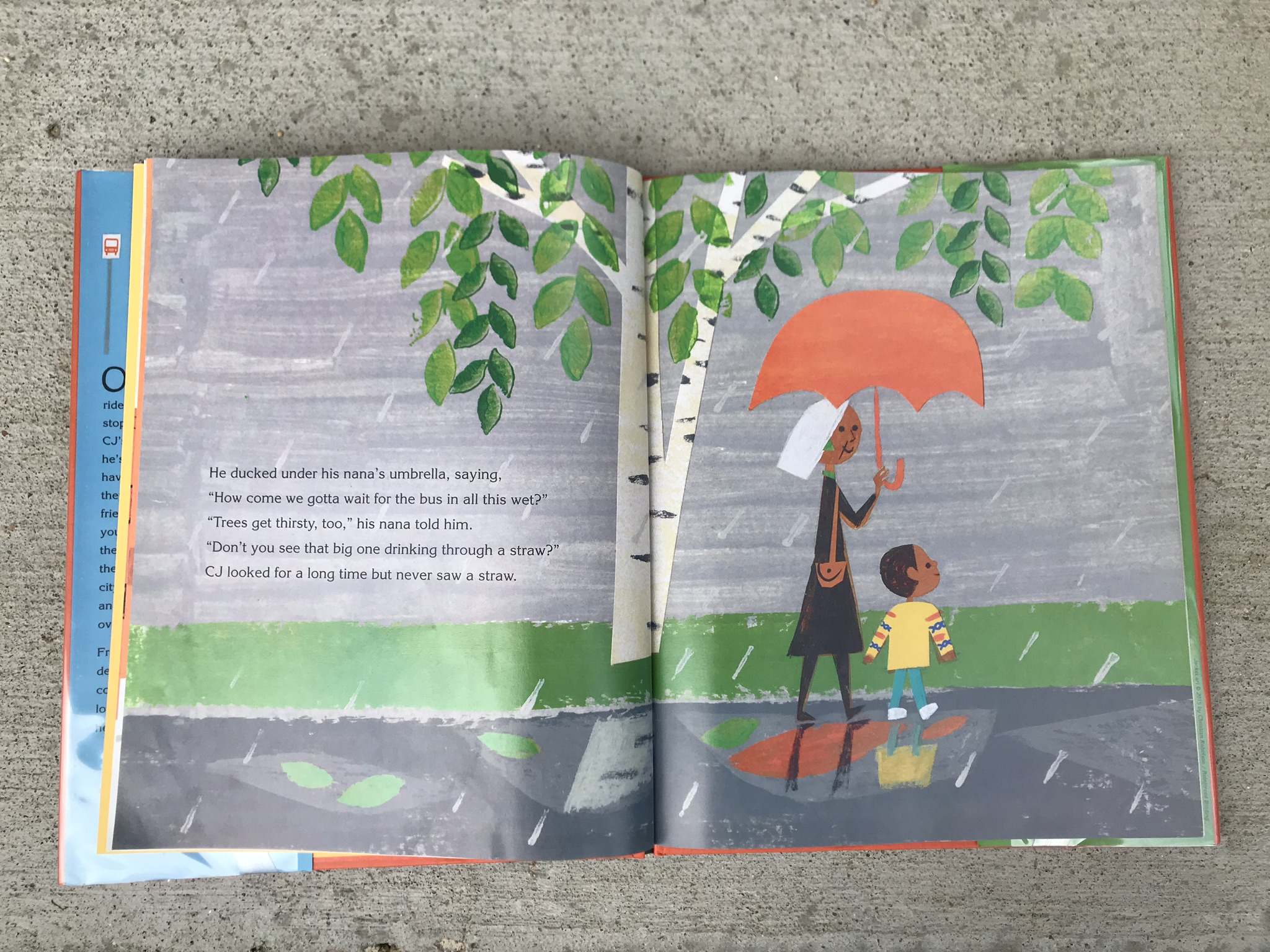

The telltale sign that separates contemporary realistic fiction from fantasy is that all of the events in the book could have actually happened. Nothing in this book is out of this world; CJ and his grandmother have regular everyday experiences in a neighborhood that could have been pulled from the streets of Denver, or any street a child might be familiar with. The focus of this book is not to tell a story about a fantastical world full of monsters and fairy-tale creatures and backdrops, but rather to tell a story that children can relate to, because it so closely mirrors an experience they could actually have, just seen from a different viewpoint. Contemporary realistic fiction resonates with readers because, “…it is the most familiar – the most accessible. This story takes place in my world. This is how I live. This book is about a girl like me. People are interested in their own lives,” (Tunnell, et al., 2016, pg 138). The illustrations in the book, though beautiful and carefully planned, are simplistic enough that they could represent a city almost anywhere. This familiarity builds a safety net for the reader. The book, because it could happen anywhere, allows the reader to feel comfortable about the story that’s about to unfold, while allowing it to have the ability to expand the reader’s limited concept of the world around them by exposing them to similar but different characters. The story starts out with the young child narrator asking his grandmother, “How come we gotta wait for the bus in all this wet?” (De la Peña, 2015). Most children have had the experience of getting caught in the rain, so they are familiar with this concept, but the book raises a new question: what is it like to get caught in the rain because you have to wait for the bus? Children who have never waited for or ridden the bus (especially in a situation outside of school) will be able to open up to this new experience by starting with the background knowledge they already have and are comfortable with, and then expanding upon it by putting themselves in the shoes of a character that reminds them of themselves.

Although we’re not sure exactly how old CJ is, he appears to be an elementary school aged child. He’s definitely not a baby or a toddler, but he’s young enough to be asking questions like, “How come that man can’t see?” (De la Peña, 2015) and to be slightly confused by his grandmother’s metaphor of the trees drinking through a straw. An important element of contemporary realistic fiction is that the story is narrated by a main character that is roughly the same age as the reader, but not younger, and that fits in this story. De la Peña’s book also ever so slightly shows the change in contemporary children’s realistic fiction which previously focus on “children in protected and positive situations,” (Tunnell, et al., 2016, pg. 140). Although the book doesn’t closely examine poverty or any kind of extreme situation, it does bring about topics of inequality (why does CJ have to take the bus when his friend has a car? Why does one area of town look dirtier than the others? Why does CJ have to work in a soup kitchen with his grandmother when his friends just go home after church?) Instead of answering these questions directly, De la Peña gives the reader a chance to look at the story and the events unfolding from a new lens and curate their own answers.

Although De la Peña’s book does not fit into a neat category, it most closely fits a problem novel. The focus of the book is not heavy, though it does ask questions that make the reader think. Tunnell, et al. explain that, “Life’s heavy challenges can appear in a book without that title being classified as a problem novel if the problem is not the major thrust of the story, even though it is present and must be faced… when the problem is not the focus, the book general is not a problem novel,” (2016, pg. 142). I wouldn’t exclusively categorize De la Peña’s book as a problem novel, but it more closely fits this category than animals, humor, mystery, school/family novels, sports, survival/adventure, or series.

Visual Elements and Visual Literacy

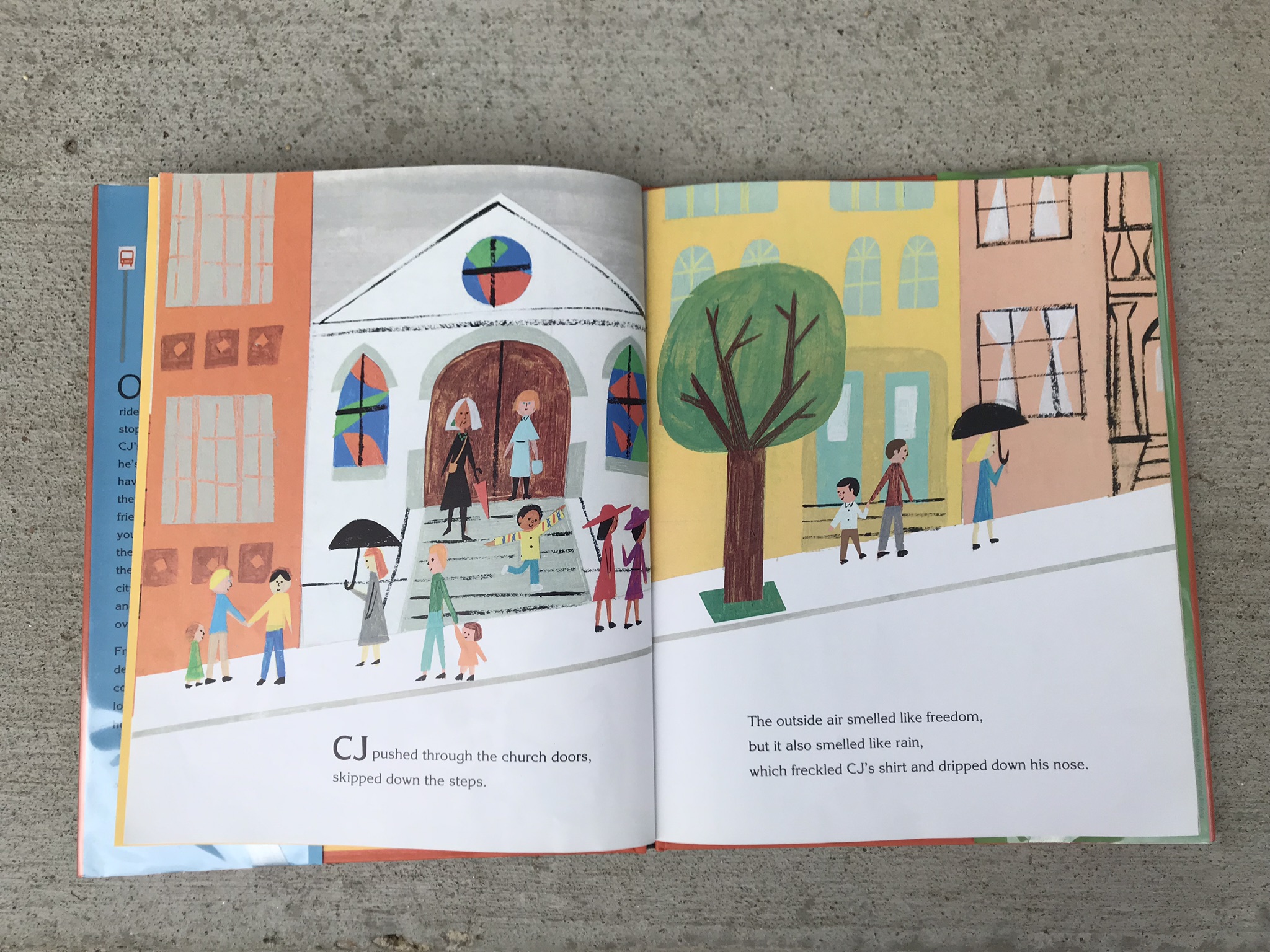

Last Stop on Market Street is a beautifully and carefully illustrated book. Robinson uses simplistic illustrations that set the scene of the book as any city, anywhere. The opening scene shows a city sidewalk with multiple buildings, a tree, and people mulling around outside of a church. Although the illustrations are not extensively detailed, this is purposeful, as it allows the reader to imagine the setting as being one they are familiar with. The reader can use their own background knowledge of a city/neighborhood and relate to it, because there is nothing specific that stands out and makes this scene different than any other.

The faces of the people are soft, and all of them are pictured with smiles. Robinson sets this stage intentionally, allowing the young reader to feel safe and at ease at the opening of the story, seeing friendly faces in a familiar place. Robinson uses many bright colors to start the book out, showing the stained glass in the windows of the church, the different colored buildings on the street, and even the different skin tones of the people walking around. The day is bright and assumed to be sunny, which is in stark contrast to the next page, where CJ is seen walking in the rain. In this illustration, the sky has turned grey, and rain splatters all around CJ and his grandmother. However, Robinson’s use of color and line here is very important – the green leaves on the “thirsty” tree stand out to the viewer, as does their bright red umbrella, and even through the rain, CJ and his grandmother are still shown smiling. Robinson uses color again to bring depth to De la Peña’s words, when he says in grandmother’s voice: “’Boy, what do we need a car for? We got a bus that breathes fire,” (2015).

Robinson has drawn a dragon on the side of the bus, breathing yellow and orange fire, which stands out from the grey and blue scene and makes the reader smile. Without this depiction, we wouldn’t know what CJ’s grandmother meant by that comment, and we wouldn’t realize that she was reminding him of the small joys in life, like a goofily painted bus with a happy and friendly bus driver inside.

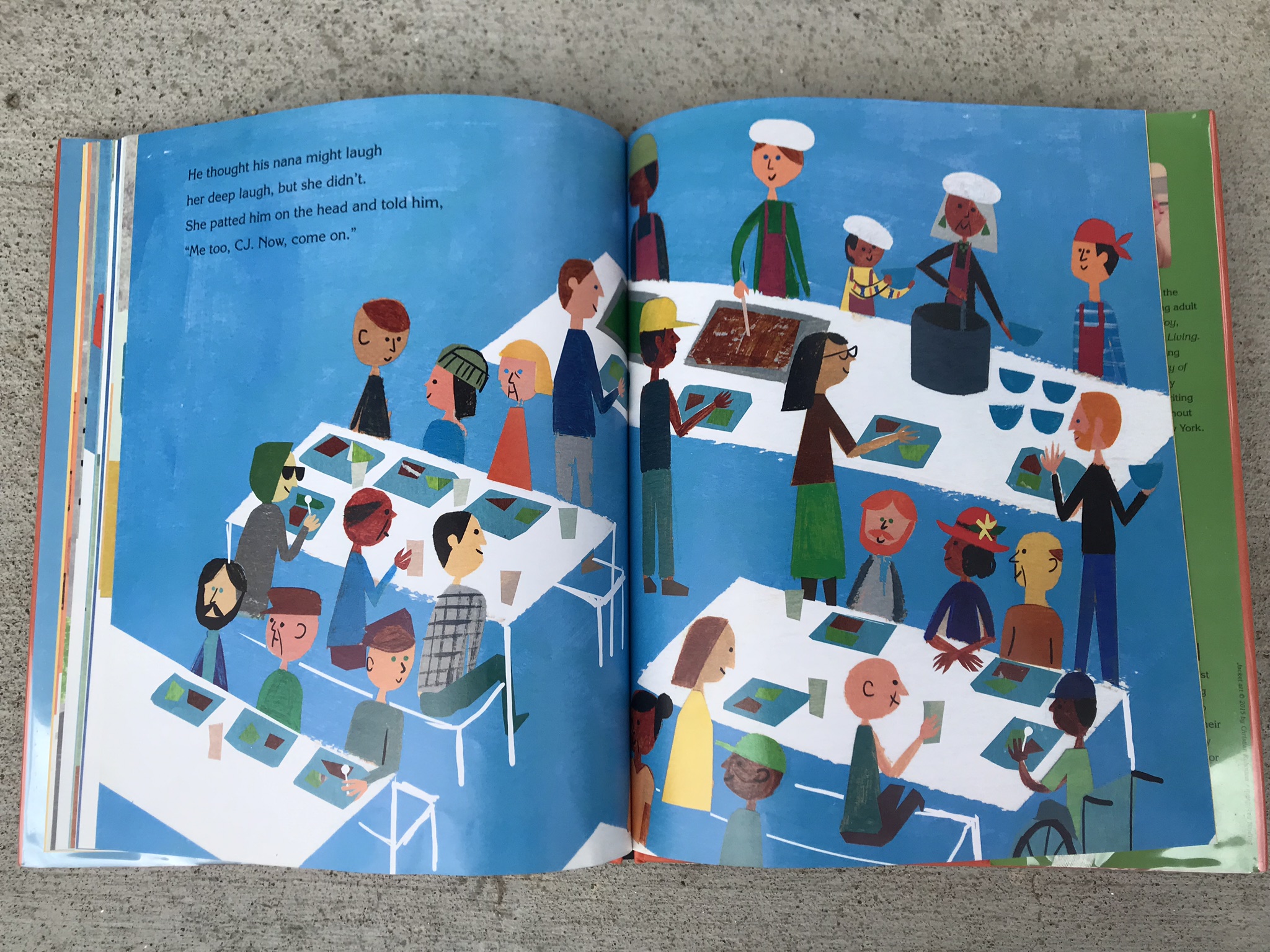

Robinson is also able to use simple illustration to draw attention to the differences between the people on the bus. He depicts a white blind man with sunglasses on and a working dog, a white old lady with a jar of butterflies, a white man with a shaved head and tattoos, and a black woman with short black hair. CJ and his grandmother have darker skin than those around them, and it’s not something that’s called attention to, but the viewer will notice the variance in skin tone of those on the bus, and will definitely notice the tattoos that snake around the man’s neck and arms. Even those who are depicted as white have a slight variance in their skin tone. Some wear glasses, some do not; some have black hair, some have grey hair, some have no hair. They all look different, but they’re all doing the same thing: riding the bus, together, to get somewhere, and listening to the music of the man with the guitar.

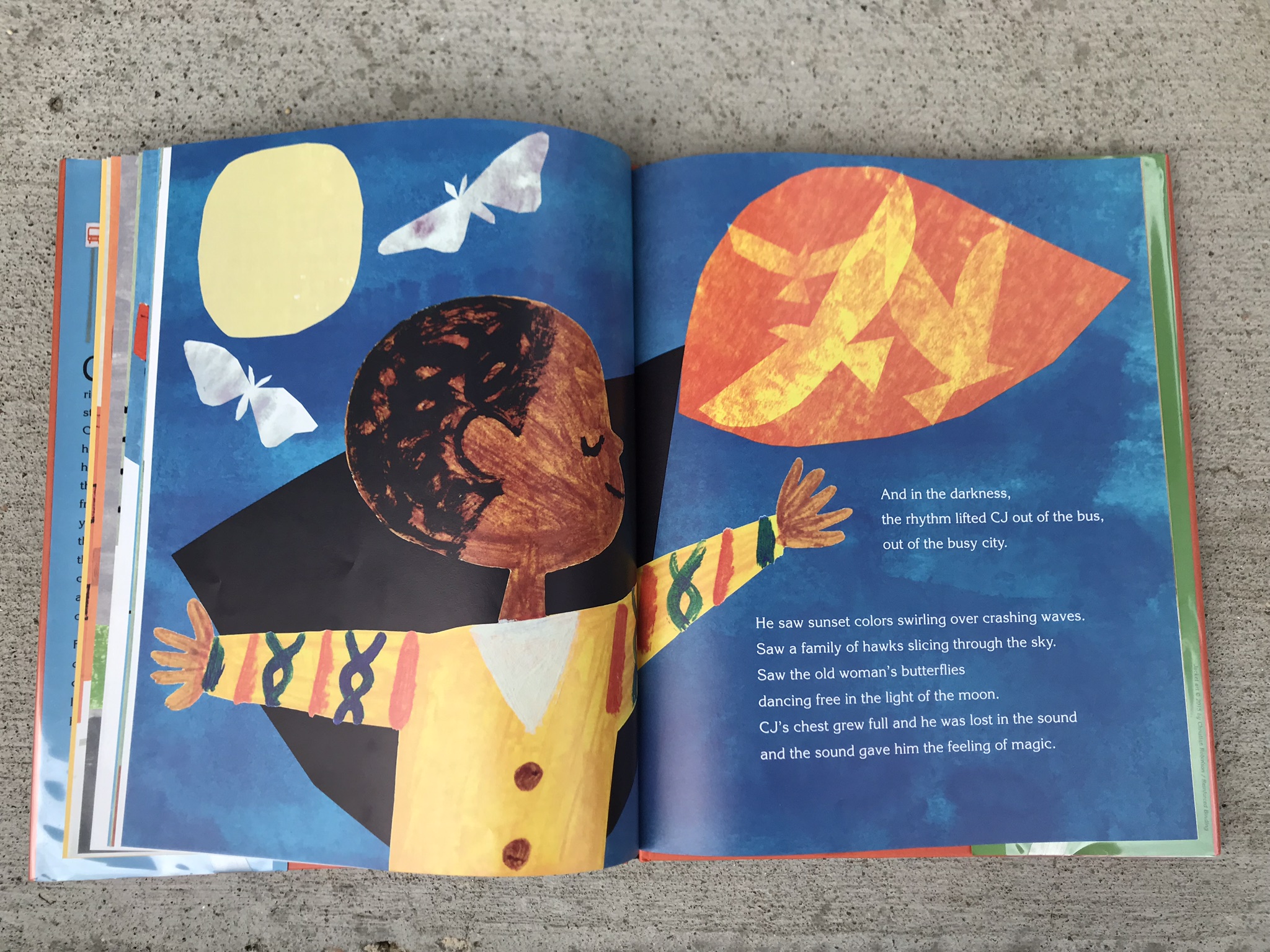

Robinson makes incredible use of color and line when De la Peña writes what CJ imagines as he hears the music: “He saw sunset colors swirling over crashing waves. Saw a family of hawks slicing through the sky. Saw the old woman’s butterflies dancing free in the light of the moon. CJ’s chest grew full and he was lost in the sound and the sound gave him the feeling of magic,” (2015). Robinson’s detailed collage scene shows the butterflies dancing in the moonlight, and the hawks inside of an orange leaf, along with CJ’s eyes closed in pleasure and smiling out of pure joy. Robinson gives us enough detail to begin to imagine the scene but also leaves it simple enough to be able to fill in the blanks with our own imagination.

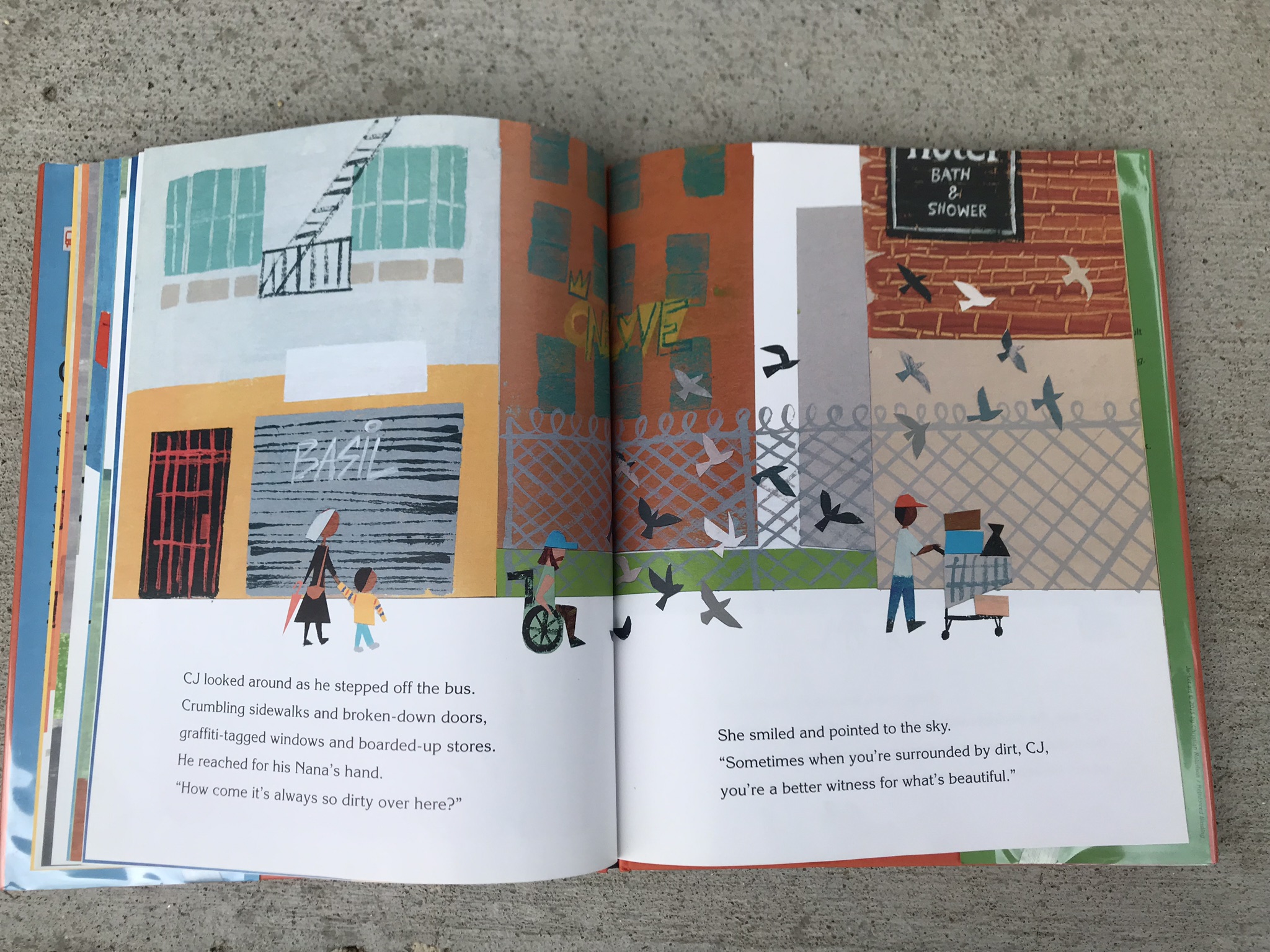

Finally, Robinson carefully draws the viewer’s eyes to what is important in the scene, and the message that De la Peña is trying to convey to the reader. For example, in the page where De la Peña describes the city as, “Crumbling sidewalks and broken-down doors, graffiti-tagged windows and boarded up stores,” (2015) our eyes are instead drawn to a flock of multi-colored birds flying off.

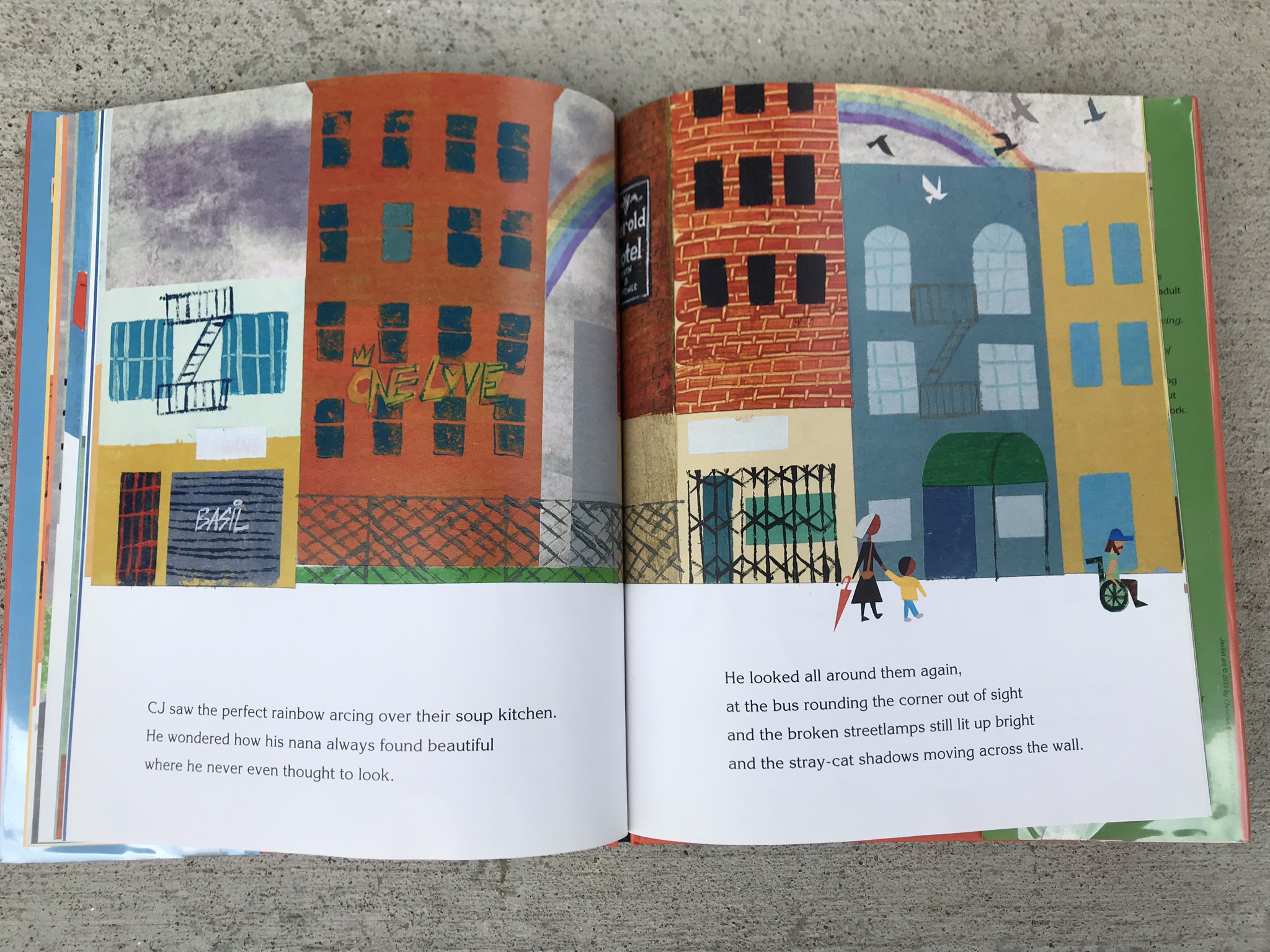

In the next page, our eyes are immediately drawn to the rainbow behind the buildings, thinking about how “his nana always found beautiful where he never even thought to look,” (2015). In every scene where CJ asks thought-provoking questions about the world around us, our eyes are drawn to smiling faces, leafy green trees, fire-breathing dragons, smiling dogs, and colorful birds, encouraging us to see beyond what we may be used to seeing, and instead to see the beautiful, where we may not previously have thought to look.

References:

Bartel, J. (2015, August 06). One Thing Leads to Another: An Interview with Matt de la Peña. Retrieved June 25, 2019, from http://www.yalsa.ala.org/thehub/2015/08/06/one-thing-leads-to-another-an-interview-with-matt-de-la-pena/

De la Peña, M. (2015). Last Stop on Market Street. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Meet the Illustrator: Christian Robinson. (2018, September 27). Retrieved June 25, 2019, from https://www.readbrightly.com/meet-illustrator-christian-robinson/

Tunnell, M. O., Jacobs, J. S., Young, T. A., & Bryan, G. (2016). Children’s Literature, Briefly (6th ed.). Upple Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.