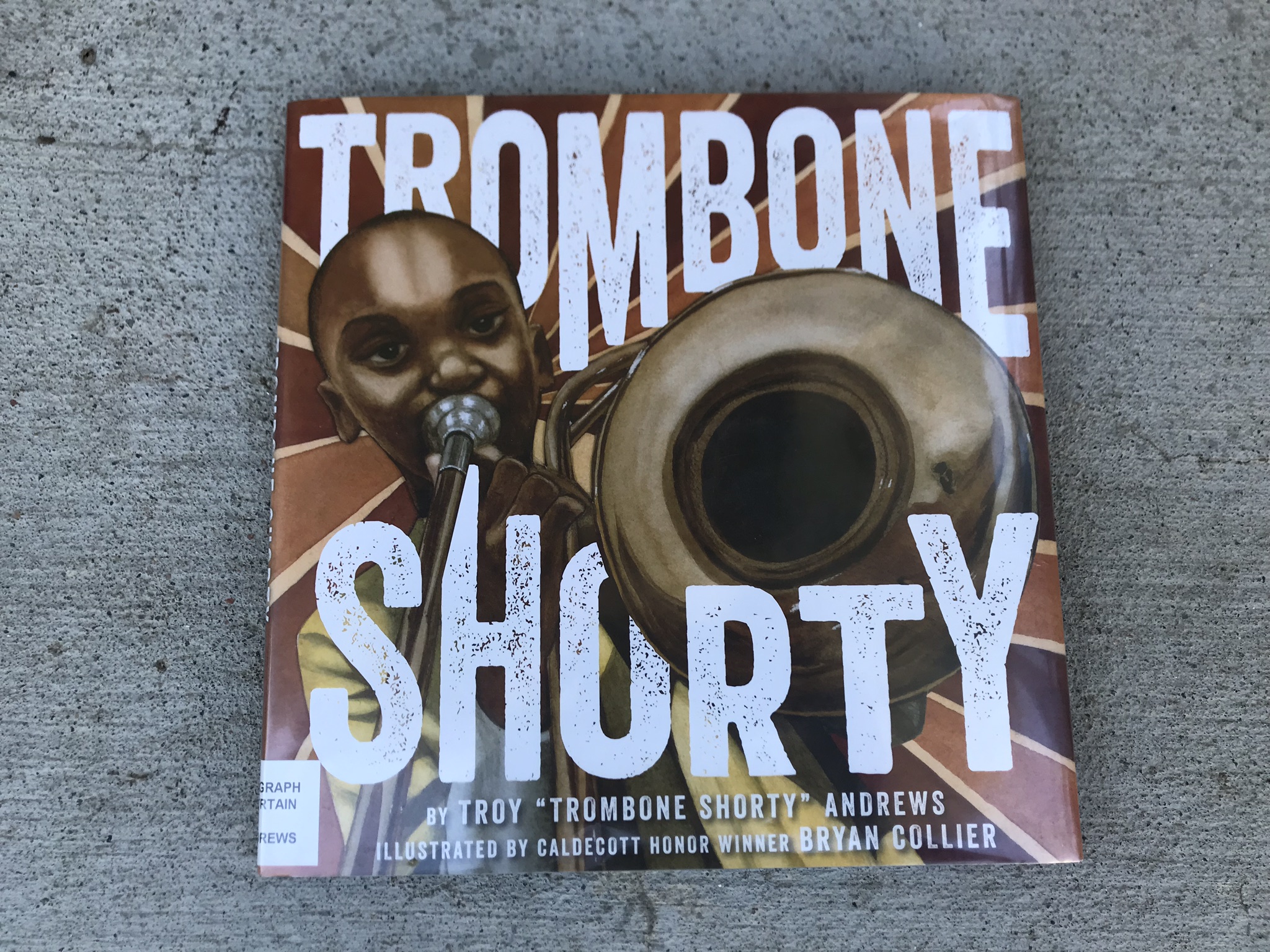

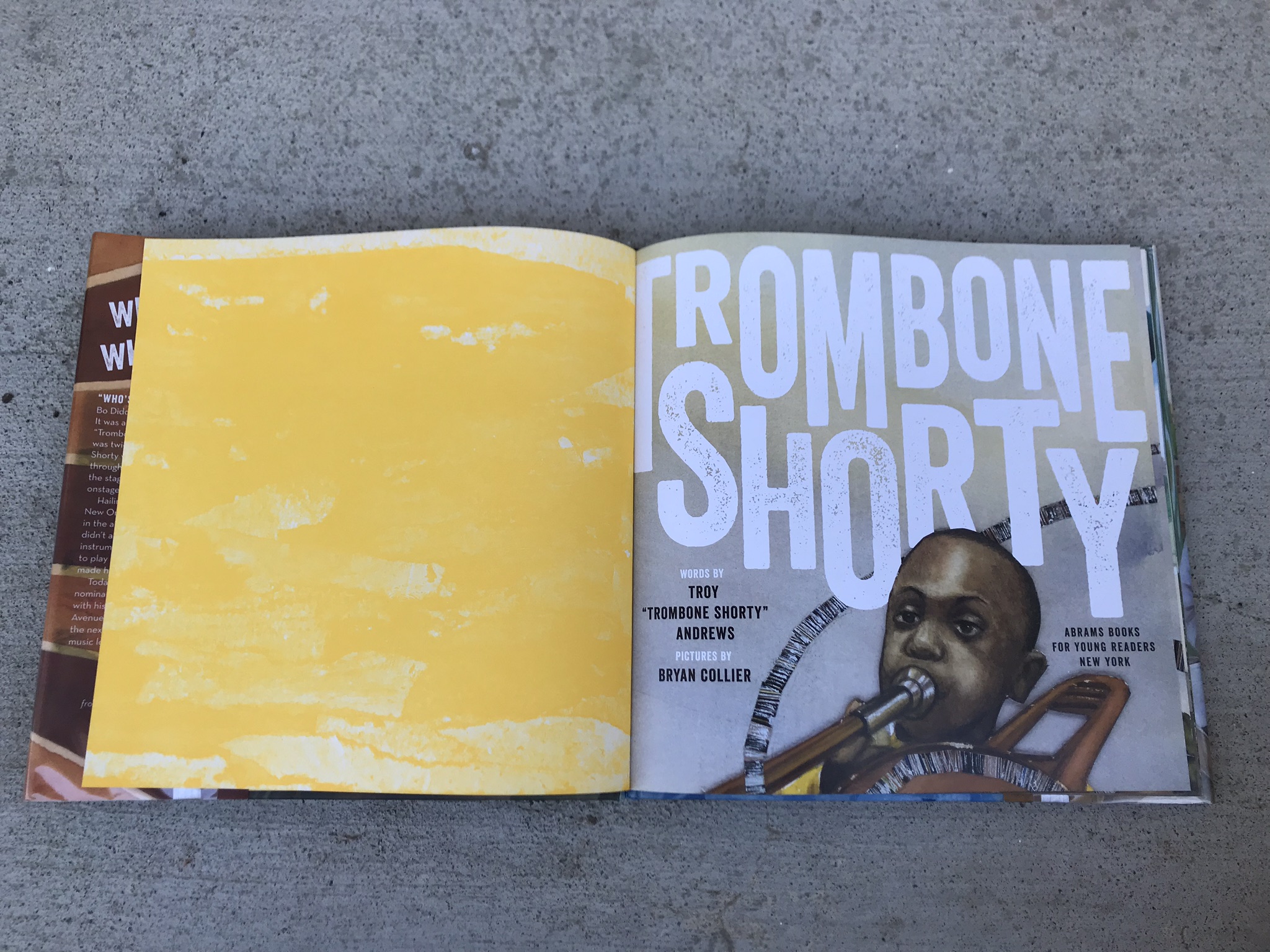

Book: Trombone Shorty, written by Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews, illustrated by Bryan Collier. A 2016 Caldecott Honor Book and Coretta Scott King (Illustrator) Award Winner.

Book type: Picture book, partial biography.

Book summary: This creatively illustrated book shows in watercolor and collage the life of Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews and how he became the renowned musician that he is today. The book focuses on his early life, how he found the original trombone he became famous for using, and how he got his nickname. The book also tells the young reader what it was like to grow up in New Orleans, the importance of music in the community, and a little bit about what the author (Troy Andrews himself!) is doing now.

Overview of the author: Andrews starts off by saying, “I like to say that the city of New Orleans raised me,” (2017). Andrews explains that music was always all around him, and that his family members were also musicians, which influenced him as well. Music made him feel connected to those around him and his community. He explains: “There were people always coming and going from my house, but music was the thing we had in common. No matter how tough things got, listening to music always made me feel better,” (2017). Andrews found community, solace, and escape in music, and he feels strongly that the tradition is carried on throughout history. To make sure of this, Andrews founded the Trombone Shorty Foundation and Trombone Shorty Music Academy, to ensure that the deep roots of New Orleans musical culture are not forgotten.

Overview of the illustrator: Bryan Collier is a notable children’s book illustrator who developed his own style of meshing watercolors along with collage. Collier earned a BA in fine arts from Pratt Institute in New York, and it was there that he became a volunteer at the Harlem Horizon Studio and Harlem Hospital Center, where he eventually became a director and inspired his “deep sense of responsibility to be a positive role model for kids,” (Collier, 2011). Although Collier says that he was also encouraged to pursue art and to read, stating: “At home and at school, I was encouraged to read. I remember the first books with pictures that I read by myself were The Snow Day by Ezra Jack Keats and Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson. I liked the stories, but I really liked the pictures,” (2011) it took him 7 years to finally get published.

Connections

Visual elements in Trombone Shorty:

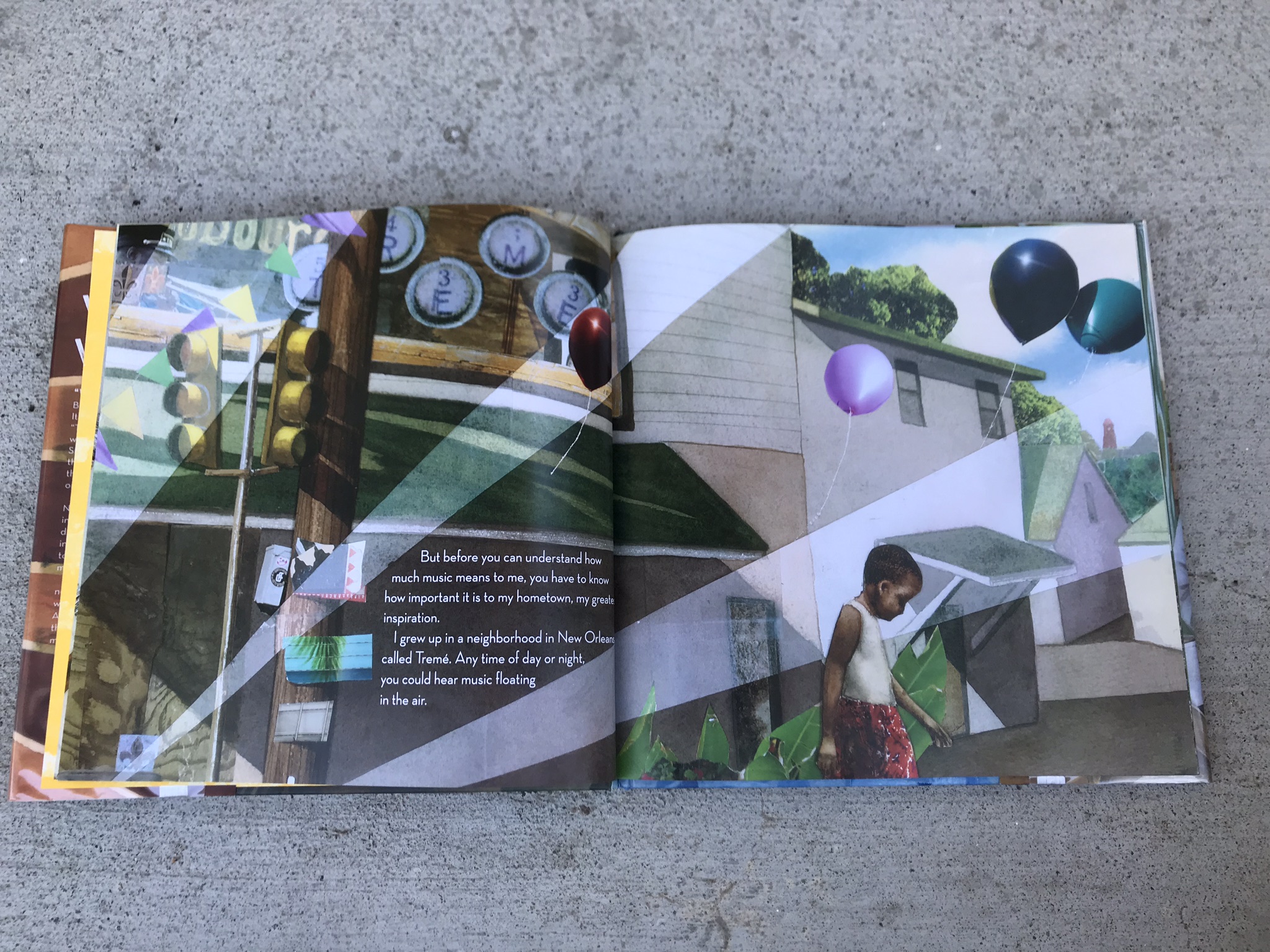

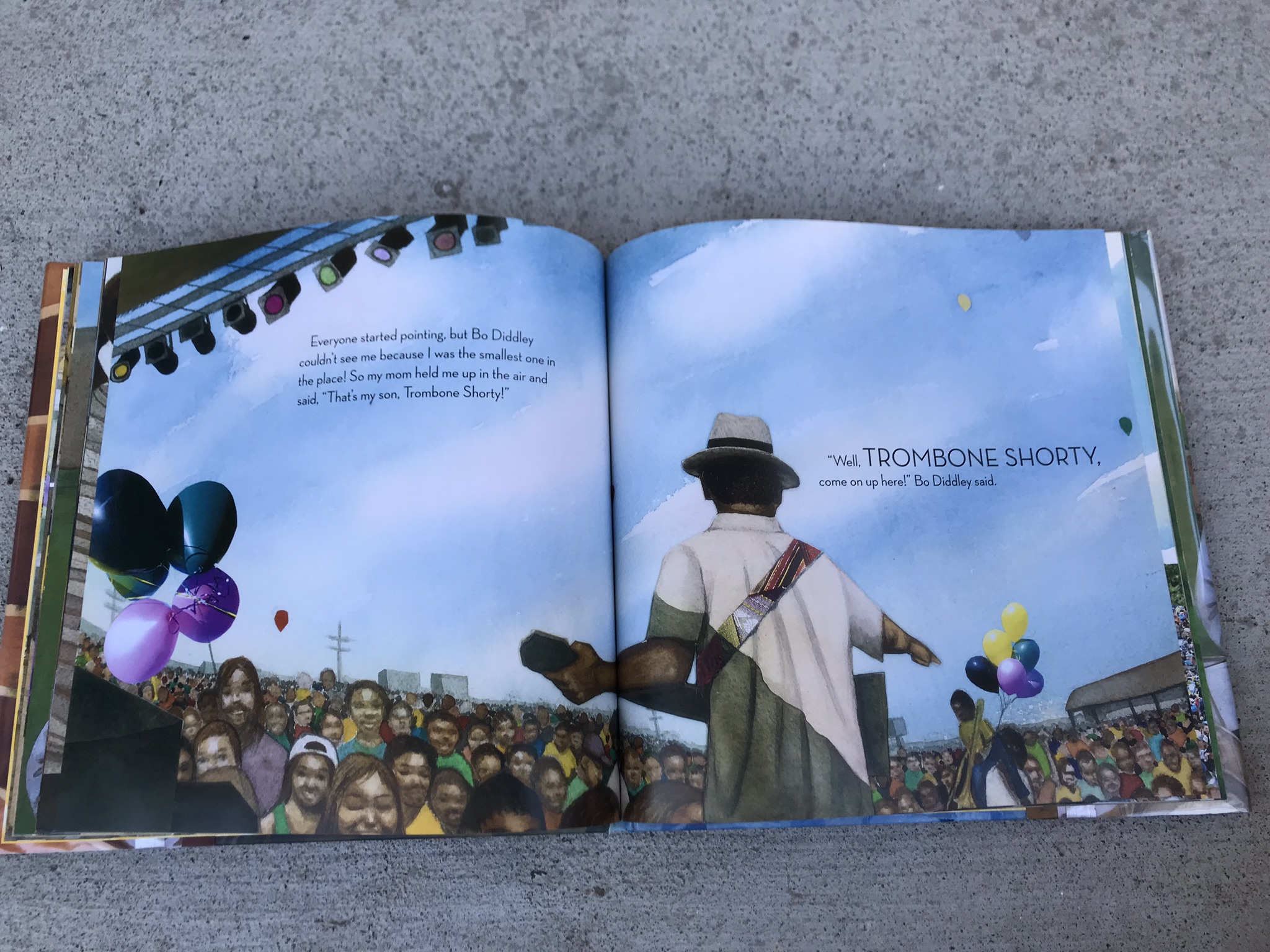

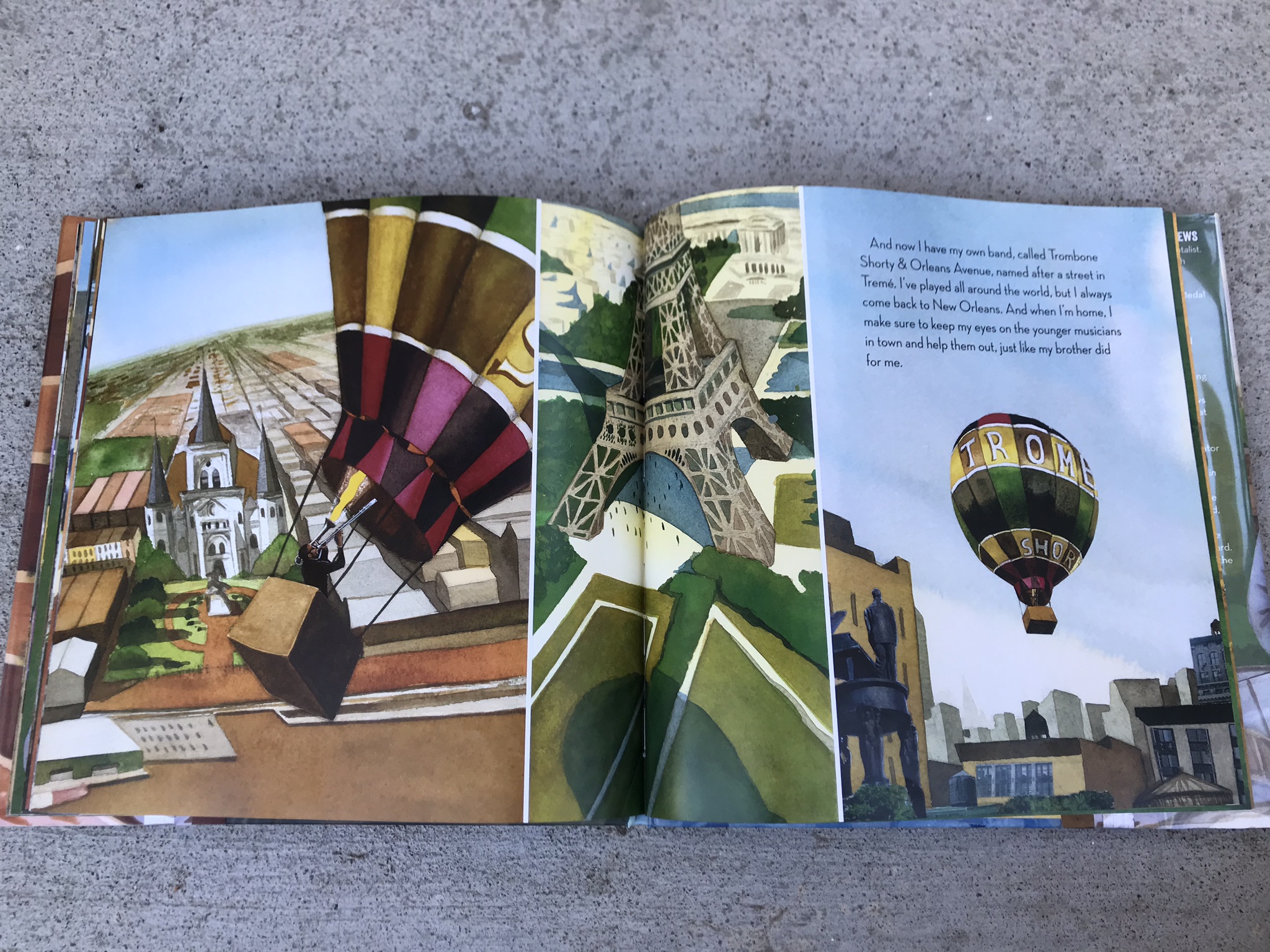

The unique illustrations in Trombone Shorty mirror the uniqueness that is New Orleans. Illustrator Bryan Collier’s mix of collage and watercolor establishes the setting in Andrew’s neighborhood of Treme, New Orleans. Andrews states, “Any time of day or night, you could hear music floating in the air,” (2017). Collier illustrates this scene by showing balloons floating through the air, representing the music being played all through the neighborhood.

Collier also uses line in his depiction of the neighborhood, cutting the scene into multiple pieces, and drawing the reader’s eyes to the little boy walking past the houses, and also to the balloons in the corner of the frame. He mixes in real photos of trees, leaves, and balloons along with painted stoplights and houses to make the scene feel just slightly dream-like. On the next page, there is a painting of Andrew’s older brother James playing the trombone, and Collier uses line to draw the viewers eyes immediately to the huge trombone and makes it look as if it is popping off the page.

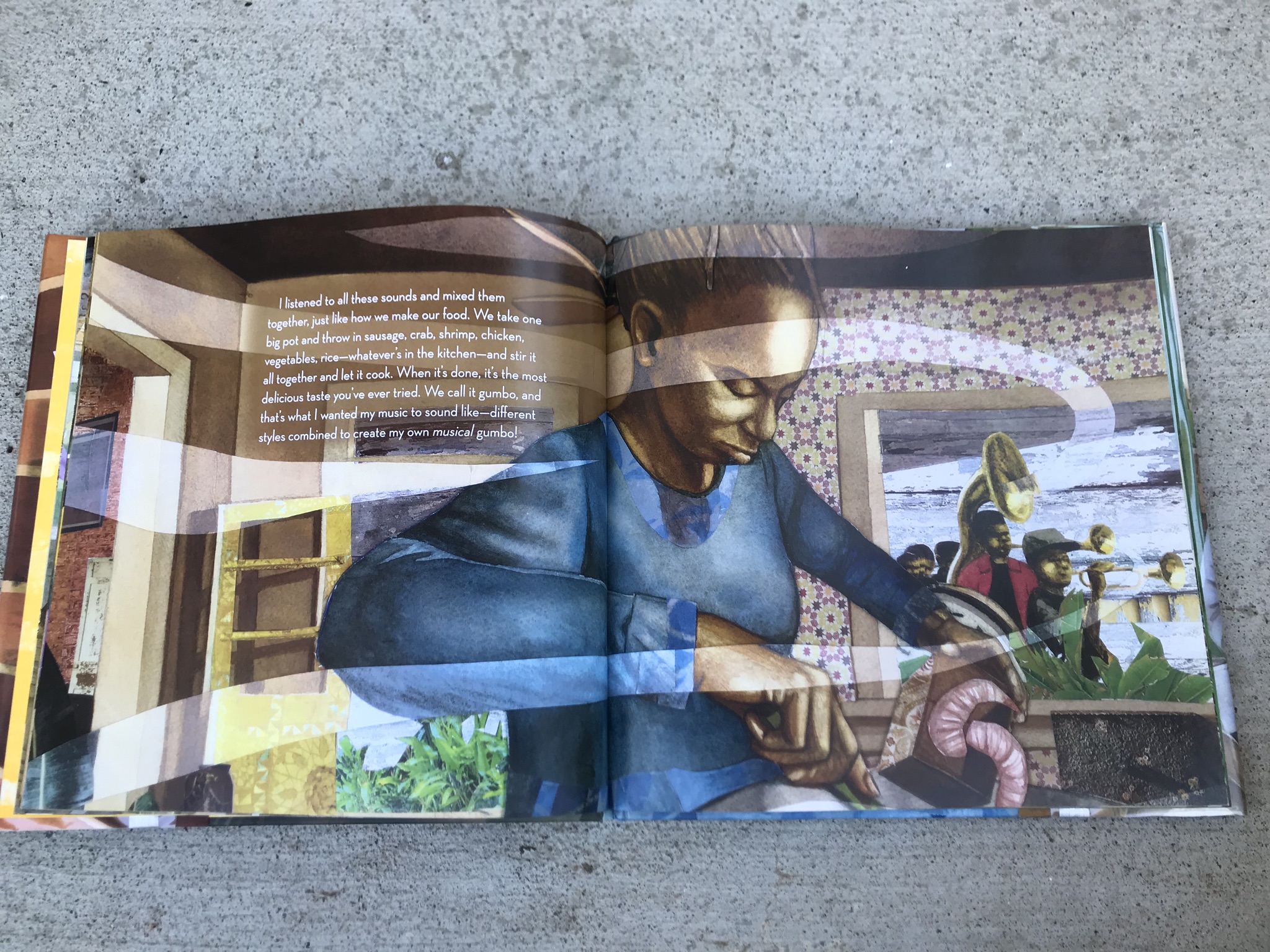

He does this again in a scene with Andrew’s mother cooking in the kitchen, using line to create swirls around the page to represent the heavenly smell of gumbo floating and swirling around in the air.

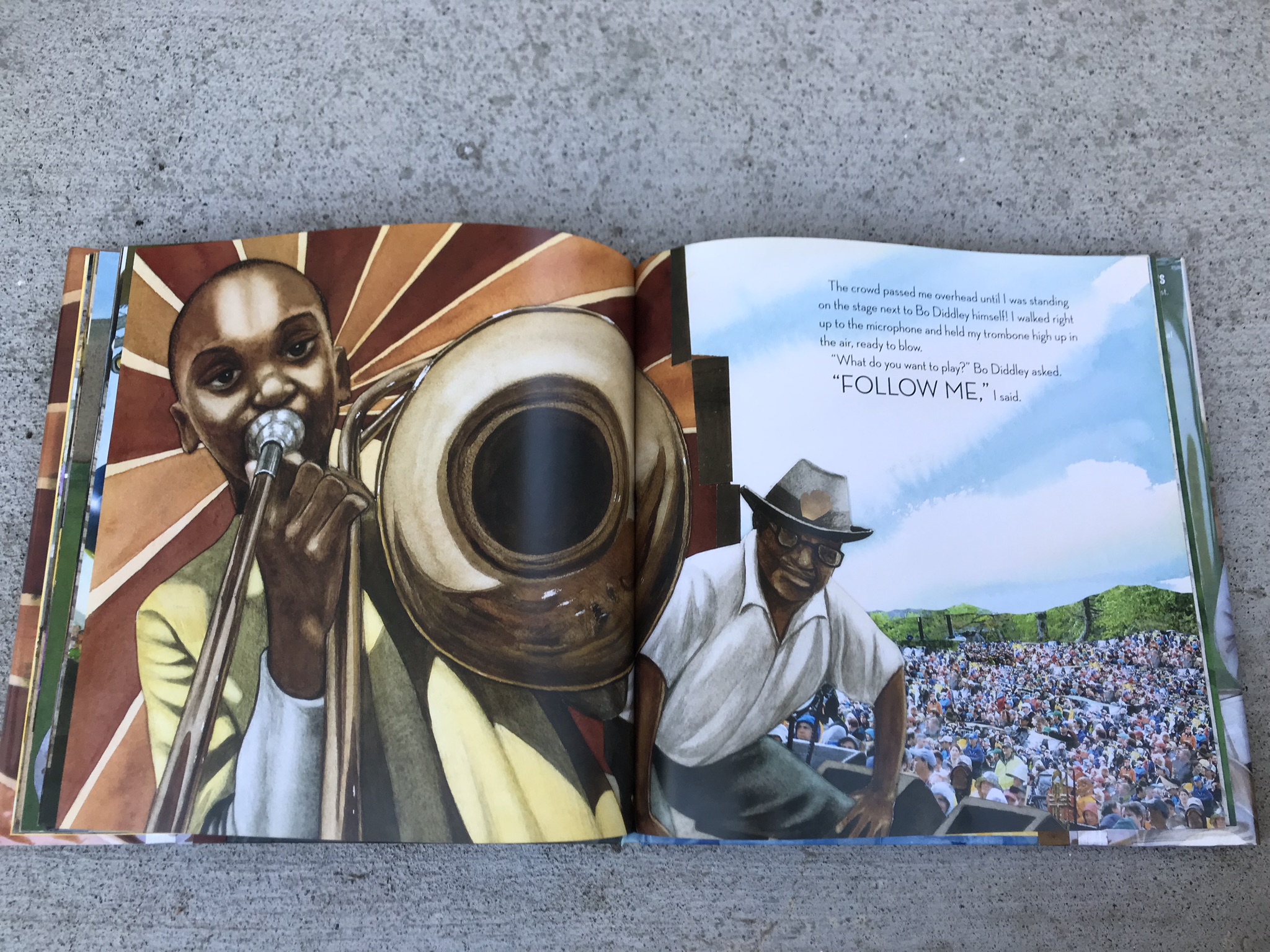

In multiple scenes where Andrew’s is in a crowd of people, Collier intersperses photos of real people along with portraits, making the reader feel as if they were really there, in a sea of people, so bustling and busy that they blur into simple colored shapes by the back.

All of the pages come alive with vibrant color, depicting everything from the multi-colored balloons in the air at festivals and parades, to the lively and bright neighborhood of Treme, and the triangles coming off of the instruments creating a feeling of pulsating musical instruments. Although the figures in the illustrations are all frozen in time, Collier depicts action subtly: hands pressed on instruments about to play, hands in air mid-clap and instruments pressed to lips.

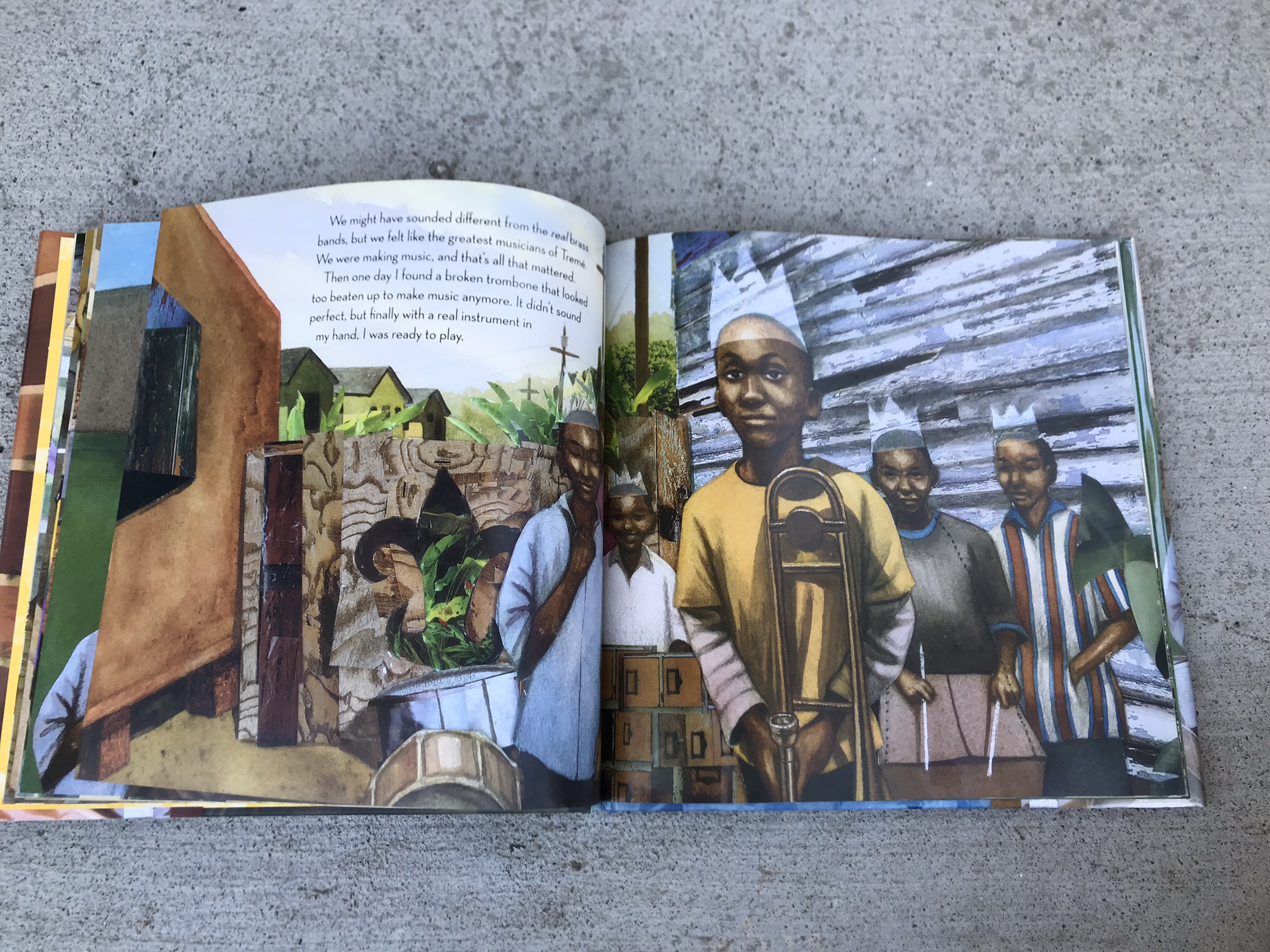

Collier also adds depth to Andrew’s words and characters, adding see-through paper crowns to the boys in the neighborhood when Andrews says, “We might have sounded different from the real brass bands, but we felt like the greatest musicians of Treme. We were making music and that’s all that mattered,” (2017). The crowns on the boys show us how they really felt: like kings of the neighborhood.

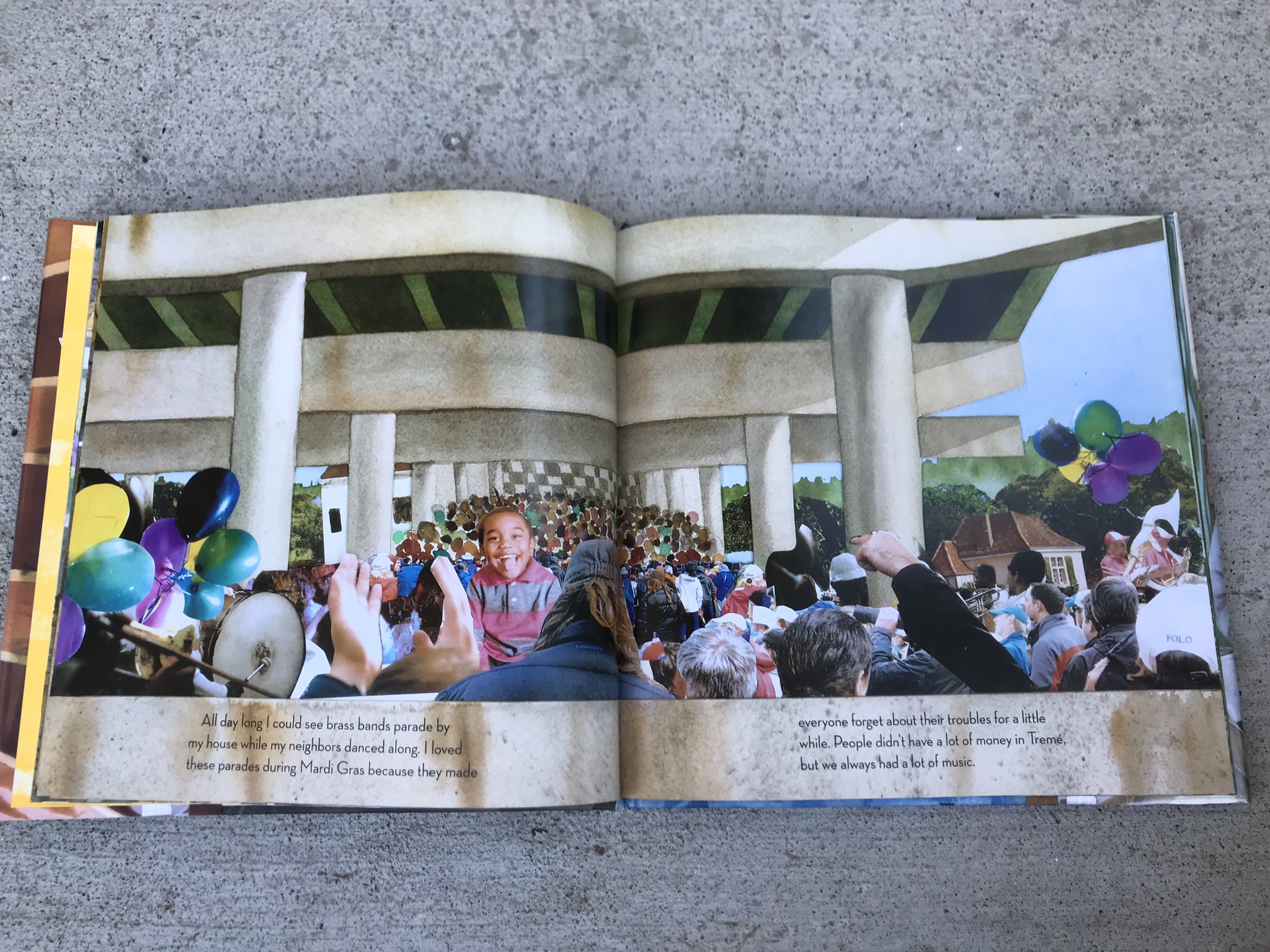

He adds a real photo of a child showing pure delight when Andrews tells us, “I loved these parades during Mardi Gras because they made everyone forget about their troubles for a little while. People didn’t have a lot of money in Treme, but we always had a lot of music,” (2017). Fingers pointing in the air, thousands of multi-colored people in the crowd, bright colored balloons, and the joy on the little boy’s face all paint the picture of how it would have really felt to have been at Mardi Gras.

Transactional Theory

Transactional theory states that, “The reader’s background, the feelings, memories, and associations called forth by the reading, are not only relevant, they are the foundation upon which understanding of a text is built. And so transactional theory invites the reader to reflect upon what she brings to any reading, and to acknowledge and examine the responses it evokes,” (Probst, 1987). Therefore, the meaning that is taken away from the text will vary considerably, depending on who is reading it. When I read this text, I found it to be an engaging biography written about someone I knew nothing about. I took an efferent stance, meaning that the meaning I found in the text was informational. Because I knew that I would be dissecting and analyzing the book after I read it, I was using it, “as preparation for another experience,” (Probst, 1987). Other readers might take an aesthetic stance, thinking about past memories of festivals and parades attended, art classes that focused on collage, and musical instruments they’d played before. They might think of times when they were trying to make their own instruments.

The meaning taken away from the text depends on what the reader intends to gain from it, and as teachers I think a lot about how often we allow students to read simply to read, and how often we ask them to read with something in mind. If I had students in a small group and before we read the book together I said, “I want you to think about the illustrations in this story and how they make you feel. What kinds of emotions do you experience? Do you feel excited? Nostalgic? Happy?” my readers would be thinking about their emotions. If I said to my students instead: “After we read this book we’re going to write a biography on Trombone Shorty,” they would be looking for information about Trombone Shorty and his experiences, prepared for another task afterward. If I said to them instead, “We’re going to read this book just for fun, and afterward I’m not going to ask you to do anything at all!” (Which I occasionally do, just so my students know we’re reading for pleasure and that it’s more than okay to do that!), they might take either stance, depending on their own preferences. If that particular student loves learning about people, they might be absorbing information about Trombone Shorty (efferent) or they may choose to focus only on the pictures (aesthetic). When readers aren’t told what to think or do, they’ll choose their own adventure. Some students may be thinking about collage and how they could create their own based on the pictures, some might think about learning how to play an instrument, some might be desperate to seek their own sources to learn more about Trombone Shorty or to hear his music. It all depends on the individual reader, as “The text is simply ink on paper until a reader comes along,” (Probst, 1987).

References:

Andrews, T. (2017). TROMBONE SHORTY. Live Oak Media.

Collier, B. (2011). Retrieved June 18, 2019, from http://www.bryancollier.com/bio.php

Probst, R. E. (1987). Transactional Theory in the Teaching of Literature. ERIC Digest. doi:ED284274